am 21.05.2024 - 08:50 Uhr

Large non-residential buildings have enormous energy saving potential. The revised EU Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD, see cci271595) and the associated Building Energy Act (GEG, German version see cci262361) take this into account and shake up operators and owners of non-residential buildings. This is because their new requirements make building automation mandatory. They stipulate that building automation and control systems as well as monitoring must be installed in all existing and new non-residential buildings with a total rated output of 290 kW or more for heating and/or ventilation and air conditioning by December 31, 2024. This includes, for example, commercial buildings, production facilities, office buildings, schools and many municipal buildings. Many property operators now need to take prompt action to digitize their buildings and increase transparency and energy efficiency. But how can property owners and administrations prepare for the requirements and implement them?

The basic prerequisite for the efficient use of building automation is that it is managed properly. It must be continuously monitored so that building use and management remain in harmony, incorrect settings can be corrected and defective systems can be identified and repaired. The first article in a new series on cci Wissensportal shows how typical errors in the management of building automation can be avoided during operation and how the requirements of the GEG for heating, cooling, air conditioning and hot water supply can be technically implemented. The specific requirements arising from the GEG for the individual trades will be shown in further specialist articles with the support of various experts from the trades concerned.

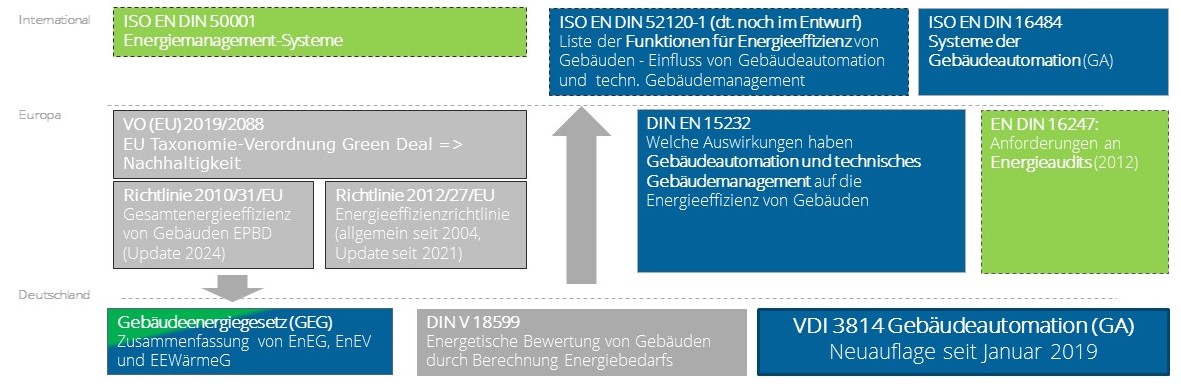

Legal framework and guidelines for building energy

International

- ISO EN DIN 50001 “Energy management systems - Requirements with guidance for use” (2018)

- ISO EN DIN 52120 Part 1, draft “Energy performance of buildings - Influence of building automation

and building management” (2018) including list of functions for energy efficiency of buildings

- ISO EN DIN 16484, Part 1, draft “Building automation systems (BA)” (2022).

Europe

- Regulation (EU) 2019/2088 EU Taxonomy Regulation “Green Deal”

- Directive 2010/31/EU (Energy Performance of Buildings Directive EPBD, update 2024)

- Directive 2012/27/EU “Energy Efficiency Directive” (EnEff-RL, 2004, update 2021)

- DIN EN 15232 Part 1 “Energy performance of buildings - Part 1: Impact of building automation and building management” (2017), including the impact of building automation and technical building management on the energy efficiency of buildings

- DIN EN 16247 Part 1 “Energy audits: General requirements” (2022).

Germany

- Building Energy Act (GEG): Combination of the Energy Saving Act (EnEG), Energy Saving Ordinance (EnEV) and Renewable Energies Heat Act (EEWärmeG), implementation of the European Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD)

- DIN V 18599 “Energy performance of buildings - Calculation of the useful, final and primary energy demand for heating, cooling, ventilation, domestic hot water and lighting” (2018)

- VDI series 3814 “Building automation (GA)” (2019)

Figure 1: There are many guidelines on the legal framework (gray) and for planning and construction (blue), but few concrete instructions, especially for the operation of buildings (green).

Savings realized in buildings by 2020

First, a brief review: According to European Union plans, energy consumption in residential and non-residential buildings across Germany should have fallen by 20% between 2008 and 2020. Only 9.7 % was achieved. The obligations resulting from the various regulations and laws to use expensive technology therefore have little effect in operation, partly because functionality is not guaranteed and checked during operation.

Three quarters of these buildings are currently not sufficiently emission-free or “climate-ready”. At present, only one percent of buildings in the EU undergo energy-efficient refurbishment each year. This means that, if the pace remains the same, only around 26% of the building stock will have been modernized by 2050.

Savings potential through building automation

Planned in accordance with the specifications of VDI series 3814 “Building Automation (GA)” (2019), all energy-related processes in buildings can be controlled. This has been the state of the art since the 1990s, although stand-alone systems from individual manufacturers have been propagated to date. This makes cross-trade and cross-system technical building management difficult. And energy savings do not happen “automatically”. Rather, it requires the interaction of all trades.

Economic efficiency

It has been proven that active energy management measures, i.e. the use of the technical possibilities of building automation for the most efficient possible control of all technical building systems in a building, bring energy savings of 5 to 20 % in line with user behavior and pay for themselves in less than two years. Source (Introduction to Building automation, controls, an technical Building Management, RHEVA Guidebook No. 22, eu.bac, 2017).

The basic prerequisite for the efficient use of building automation is that it is managed sensibly. It must be continuously monitored so that building use and management remain in harmony, incorrect settings can be corrected and defective systems can be detected and repaired. A poorly managed building consumes 30 % more energy and emits 30 % more CO2 than a building that is optimally managed (source: REHVA - eu.bac, Hans Kranz, Introduction To Building). Unfortunately, poor management is still the reality in many non-residential buildings today.

Typical errors in operation

The following examples of typical errors show the challenges of managing building automation in operation:

GEG requirements for heating, cooling, air conditioning and hot water supply

The Building Energy Act is now intended to provide a remedy. It applies to residential and non-residential buildings and is a summary of previously applicable laws (Energy Saving Act (EnEG), Energy Saving Ordinance (EnEV) and Renewable Energies Heat Act (EEWärmeG)). It also transposes the requirements of the European Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) from 2018 into national law. In particular, the GEG regulates

Requirements for new and existing buildings with regard to the standards for low(est) energy (kWh/(m²*a) including the corresponding calculation bases and procedures

Specifications for the construction, renewal and operation of heating, cooling and ventilation systems as well as hot water supply in residential and non-residential buildings (“Heating Act”)

Preparation of energy performance certificates

The GEG thus also sets out specific legal requirements that apply to the operation of buildings and makes non-compliance with these requirements punishable in some cases.

As energy systems are becoming increasingly complex, some requirements for heating, cooling and ventilation technology as well as hot water supply in non-residential buildings can hardly be met without networked building automation. These are set out, for example, in the GEG:

It is worth noting that the current GEG dedicates a separate paragraph to building automation in §71a. This contains extensive specifications for the operation of larger non-residential buildings (from 290 kW thermal connected load). These specifications are not easy to implement, but require building automation to be carefully planned and implemented.

Implementation of the GEG: What exactly needs to be done?

Section 71a, paragraph 2, sentence 2, requires that “the collected (energy) data is made accessible via a common and freely configurable interface so that evaluations can be carried out independently of the company and manufacturer”.

a) Ensuring open interfaces

Exactly what this interface must look like is not specified. The most reliable way to ensure that this is company- and manufacturer-independent is via a manufacturer-neutral management level. Such systems dispense with proprietary data storage and serve all standard market interfaces per se.

b) Ensure interoperability, for example via BACnet

Paragraph 71a requires in section 3 that newly constructed non-residential buildings must be equipped with a building automation system. It must be “ensured that this system enables communication between interconnected technical building systems and other applications within the building and can be operated together with other types of technical building systems, even with different proprietary technologies, devices and manufacturers.” Paragraph 4 extends this requirement to existing buildings that are already equipped with a building automation system. These buildings must ensure the communication of interconnected technical building systems by December 31, 2024 or must be retrofitted accordingly. This means that an open, manufacturer-independent communication protocol such as BACnet, KNX or ModBus is effectively prescribed for new buildings. The required interoperability can only be guaranteed with devices that use such protocols for communication. For existing buildings, this means that proprietary protocols must be upgraded via gateways to ensure that the building technology systems can communicate with each other.

c) Set specifications for interoperability, for example through the BACtwin

With KNX, interoperability is simply guaranteed, but the applications are largely limited to room automation. It has become clear to many operators in recent years that BACnet is not the same as BACnet, as proprietary interpretations stand in the way of the manufacturer-neutral expansion of systems, cross-trade energy management and the coordination-free digitalization of processes in technical building management. Especially if they are responsible for larger real estate portfolios. Many proprietary manufacturers have sold BACnet solutions that do not enable true coordination-free interoperability of technical building systems, unless all systems are automated with the same manufacturer. The situation is similar with ModBus. Here too, communication is basically open, but the implementation of interoperability requires even more specifications on the part of the building owner. This is why many operators of larger real estate portfolios draw up building automation specifications in order to set out the most important requirements. If you want to be sure that your building automation meets the interoperability requirements of the GEG, you should take up the specifications for BACtwin recently published by the AMEV and formulate your BACnet specifications on this basis. This can be the basis for both new and existing buildings. Another pleasant side effect: BACtwin also creates a solid basis for coordination-free interfaces to other systems in the course of digitalization, for example technical monitoring, maintenance management or ESG reporting (environmental, social and corporate governance).

Preview: Parts 2 to 4 of the series on the technical implementation of the GEG requirements for building automation

The specific requirements arising from the GEG for the individual trades will be shown in further specialist articles with the support of various experts from the trades concerned.

GEG requirements for cooling and ventilation systems: Prof. Christoph Kaup, Chairman of the Fachverband Gebäude-Klima (FGK), Ludwigsburg, and Managing Director of Howatherm Klimatechnik GmbH, Brücken

Requirements for heating and hot water supply systems: Prof. Michael Krödel, Director of IGT - Institute for Building Technology GmbH, Neubiberg

Requirements for energy management and building automation management: Christian Wild (see below) and Christoph Zeis, Managing Director of Energiedienstleistungsgesellschaft Rheinhessen-Nahe GmbH, Nieder-Olm

Powered by ModuleStudio 1.3.2