am 17.06.2024 - 10:45 Uhr

The Building Energy Act (GEG) also applies to cooling and ventilation systems and equipment. According to Part 4 of the GEG, these systems may not be modified if they contribute to the energy quality of the building (Section 57). In addition, they must be kept ready for operation (§ 58) in order to ensure that they are used as intended. The operator must operate the systems properly (§ 59) and ensure maintenance and servicing (§ 60).

The main focus here is on the energy efficiency of the systems. The energy requirement of the systems is essentially determined by two areas: the electrical energy requirement and the thermal energy requirement, which is necessary to heat and cool the outside air to the desired supply air condition. Added to this is the energy required to humidify and/or dehumidify the air.

Example of a central roof unit: From around 60,0000 m³/h (290 kW), the requirements of the GEG for building automation apply (Fig. © Howatherm)

Cooling and ventilation systems and equipment must be designed in such a way that the limit value for the specific fan power in accordance with category 4 of DIN EN 16798 Part 3 “Energy performance of buildings - Ventilation of buildings: Ventilation of non-residential buildings - Performance requirements for ventilation and air conditioning systems and room cooling systems” (2017) is not exceeded at the design volume flow rate. This concerns

the installation of an air conditioning system with a rated output for more than 12 kW cooling demand

ventilation and air conditioning systems with supply and exhaust air function that are designed for a supply air volume flow of at least 4,000 m³/h

the renewal of a central unit or air duct system of such a system

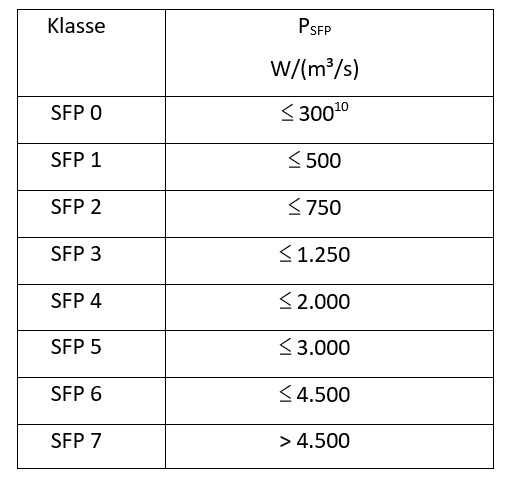

The electrical power consumed by the entire HVAC system is defined by the SFP classes of DIN EN 16798 Part 3. The specific fan power describes the electrical power consumption required to convey an air volume flow of 1 m³/s. The SFP value is proportional to the pressure drop and inversely proportional to the system efficiency ηS, which is calculated by multiplying the individual efficiencies of the components used. Since the Energy Saving Ordinance (EnEV) 2009, corresponding HVAC systems must comply with a maximum specific fan power of 2,000 W/(m³/s) corresponding to SFP class 4 (Specific Fan Power) in accordance with DIN EN 16798 Part.

Classification of the specific power consumption SFP (source: DIN EN 16798 Part 3)

Additional SFP allowances in accordance with DIN EN 16798 Part 3, Section 9.5.2.2, can be taken into account for HEPA filters, gas filters and heat recovery components of classes H2 or H1 in accordance with DIN EN 13053 “Ventilation for buildings - Central ventilation units - Performance characteristics for units, components and assemblies” (2020), as these components are not part of the standard equipment of ventilation and air conditioning systems.

In addition, from January 1, 2023, the permissible primary energy requirement for buildings to be constructed is to fall from the previous 75 % to 55 %, meaning that the aforementioned SFP values must fall by 45 %. In order to be able to estimate the energy requirements of ventilation and air-conditioning technology, particularly in non-residential buildings, for Germany, the distribution of the installed ventilation and air-conditioning units with their volume flows to be conveyed must be considered. A study carried out by the author at the Environmental Campus Birkenfeld of Trier University of Applied Sciences shows the following for HVAC systems in Germany:

The volume flow distribution shows that around 30 % of all HVAC systems with air volume flows of less than 4,000 m³/h, which are mainly installed in non-residential buildings, are not affected by the GEG. It is also clear from the air volume distribution that the average air volume flow is around 7,400 m³/h, while the median of the heating work shifts to around four times this value of 28,800 m³/h. The study also revealed that the relevance of systems below 4,000 m³/h (30 % of all systems) in terms of energy demand is only 4 %, while 70 % of these systems have an energy relevance of 96 %.

HVAC systems with an air flow rate of up to 4,000 m³/h are not subject to the GEG. Here is an example of a central system in a hospital. (Image © Howatherm)

If the electrical energy consumption of the systems is reduced, enormous potential savings can be made in the area of ventilation and air-conditioning technology. Basically, three factors determine the electrical energy requirement, based on the electrical power consumption (Pm) of an air conditioning system:

Pm = qV - Δp / ηS where:

qV: conveyed volume flow in m³/s

Δp: Total pressure difference in Pa

ηS: System efficiency of the fan drive system

The relationship between these factors shows that there are basically three ways to influence the electrical energy requirement of a system:

Reduce the air volume flow. However, this is essentially determined by the application itself.

Reduce the differential pressure to be overcome by the fan in the system. This is determined by the installed components of the air handling unit and the connected air duct network. Reducing the air velocity by just 10 % can reduce the differential pressure to be overcome by around 20 %. The electrical power consumption is even reduced by around 33 %.

Increase the system efficiency (ηS) of the fan drive system. This is determined by the four individual efficiencies of the fan, motor, drive and speed control. The energy requirement can be influenced most strongly with the speed control of the fan, as the power consumption changes with the third power of the speed or the volume flow (see § 67 below in the text).

Direct-driven free-running fan (Fig. © Howatherm)

Insofar as a system pursuant to § 65 GEG is intended to directly change the humidity of the room air, this system must, when installed in a building and when the central unit of such a system is replaced

be equipped with an automatic control device,

in which separate setpoints can be set for humidification and dehumidification

and at least the directly measured supply or extract air humidity serves as the reference variable.

If such equipment is not available in an existing system, the operator must retrofit it within six months of the expiry of a period of six months in accordance with Section 76 GEG.

The energy required to condition the supply air corresponds to the change in enthalpy of the air conditions. If, for example, air at 20 °C is humidified or dehumidified by 3 g/kg, the latent energy content is 7.6 kJ/kg, which corresponds to a sensible temperature change (heating or cooling) of around 7.5 K. This example clearly shows that humidifying and/or dehumidifying the air is energy-intensive. The relevant requirements of the GEG are therefore to be welcomed

When installing a system in accordance with § 65 GEG and when replacing a central unit or an air duct system of such a system, it must be equipped

with an automatic regulation of the volume flows depending on the thermal and material loads or

with a device for adjusting the volume flows as a function of time if the supply air volume flow of this system is greater than 9 m³/h per square meter of net floor area supplied to the non-residential building.

Rooms should undoubtedly be supplied with healthy outside air. In many buildings, mechanical ventilation and air conditioning systems are used for this purpose, which replace CO2-polluted indoor air with outdoor air. In addition, the dilution of the air reduces germs and pollutants in the room and limits the CO2 content. Modern air conditioning systems are therefore often controlled via the CO2 content in the room air, as it is used as a measure of the occupancy of a room and to assess the room air quality. A CO2 concentration of up to 1,000 ppm is still considered acceptable. It is therefore advisable to operate the systems according to demand rather than constantly. As the speed decreases, the power consumption of the drives is reduced to the third power. If, for example, only 50 % of the designed volume flow is required in partial load operation, the electrical power consumption drops to around 13 % of the original nominal output with a constant system characteristic curve.

This is why variable speed control systems that can operate systems according to demand have now become established. The great benefit of this far outweighs the disadvantage of the approximately 4 % efficiency loss of speed control. With integrated speed control systems, it is also possible to measure and display the volume flow (actual value) in the inlet nozzle of the fan and use it for control purposes.

If a system is installed in buildings in accordance with § 65 GEG or a central unit of such a system is replaced, it must be equipped with a heat recovery system. This does not apply to applications in which the recovered heat cannot be used or the supply and exhaust air systems are physically separated. The heat recovery device must at least comply with classification H3 in accordance with DIN EN 13053. For the number of operating hours, the boundary conditions of use according to DIN V 18599 Part 10 “Energy performance of buildings - Calculation of useful, final and primary energy requirements for heating, cooling, ventilation, domestic hot water and lighting: boundary conditions of use, climate data” (2018) and for the air volume flow rate, the outside air volume flow rate are decisive.

The quality and efficiency of a heat recovery system are largely determined by the degree of temperature change, also known as the heat recovery coefficient (Φ). In addition to the degree of temperature change, the efficiency of a heat recovery system is determined by the pressure losses on the media sides. The media-side resistances of the heat recovery unit therefore play a major role, particularly on the supply and extract air sides. The auxiliary energy required to use the heat recovery system is essentially determined by the electrical drives, for example fans, which have to be operated with more power to provide auxiliary energy, and other consumers such as pumps. The heat recovery system is regulated by the degree of temperature change. In addition to the benefit in the form of recovered heat, the electrical energy used to overcome the flow resistance caused by the equipment must also be considered.

Since the introduction of the Energy Saving Ordinance (EnEV 2009), heat recovery has been classified in accordance with DIN EN 13053 (2007). The EnEV (and subsequently the GEG) still refers to DIN EN 13053 from 2007, as the heat recovery specifications were discarded in the later versions of the standard and the energy efficiency factor ηWRG was introduced in its place. The old version was completely withdrawn. However, as economic efficiency criteria were no longer included in the subsequent standard, the GEG still refers to the 2007 standard.

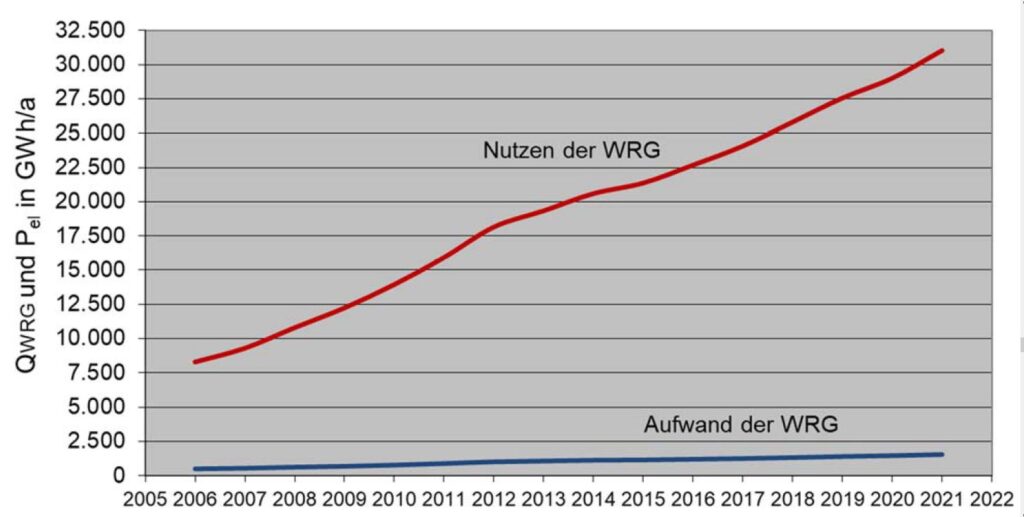

Cumulative values for the benefits of heat recovery (thermal work) and the costs (electrical work) for the years 2006 to 2021 (Fig. © Kaup)

Cumulative values for the benefits of heat recovery (thermal work) and the costs (electrical work) for the years 2006 to 2021 (Fig. © Kaup)

For the year 2030, an annual heat supply of around 46 TWh can be estimated for non-residential buildings. The electricity required to operate these heat recovery systems will then amount to around 2.2 TWh/a. This results in an average coefficient of performance of just under 21 for the heat recovery systems. The primary energy saving is therefore expected to be 46.7 TWh/a and the annual CO2 saving around 12.7 million tons.

A non-residential building with a rated ventilation system output of more than 290 kW must be equipped with a building automation and control system in accordance with paragraphs 2 to 4 by December 31, 2024. Sentence 1 shall also apply to a non-residential building with a rated output for an air conditioning system or a combined air conditioning and ventilation system of more than 290 kW. In order to meet the requirement in the first paragraph, a non-residential building must be equipped with

digital energy monitoring technology, by means of which continuous monitoring, logging and analysis of the consumption of all main energy sources and all technical building systems can be carried out, the collected data can be made accessible via a common and freely configurable interface so that evaluations can be carried out independently of the company and manufacturer, requirement values can be established with regard to the energy efficiency of the building, efficiency losses of technical building systems can be recognized and the person responsible for the facility or technical building management can be informed about possible improvements in energy efficiency.

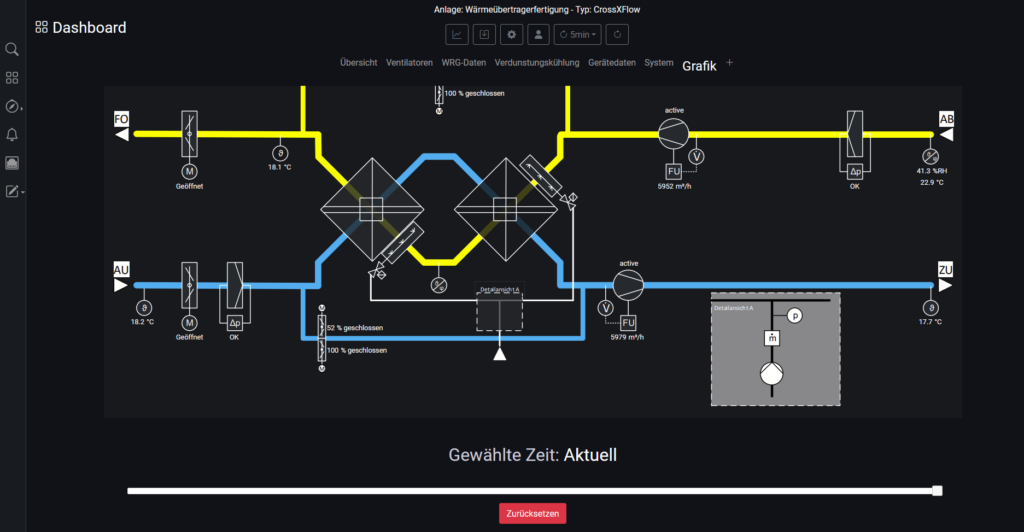

Monitoring an air conditioning system with heat recovery (Fig. © Howatherm)

Monitoring an air conditioning system with heat recovery (Fig. © Howatherm)

Section 71a GEG makes it clear what influence building automation will have in the future. In their own interests, operators should also be interested in being continuously informed about the status of their systems. Especially as malfunctions can cause considerable energy losses. Continuous monitoring of the systems makes sense, as malfunctions can be noticed immediately and rectified in good time.

In order to meet the requirements of the GEG, the energy-efficient control of HVAC systems is becoming increasingly complex. Air handling units should be equipped with their own controllers, as the manufacturer has the necessary expertise in process engineering. Furthermore, these control systems must be able to be integrated into the automation system of the entire building with open, standardized interfaces with as little coordination as possible. BACnet in combination with the BACtwin specification could be an effective way to achieve this.

Operators of an air conditioning system or combined air conditioning and ventilation system installed in a building with a rated output for cooling requirements of more than 12 kW must have energy inspections of these systems carried out by an authorized person within the meaning of Section 77 GEG within the periods specified in Section 76 GEG. An operator may fulfill this obligation by means of a random inspection in accordance with § 75 GEG if he operates more than ten air conditioning systems or combined air conditioning and ventilation systems that are installed in comparable non-residential buildings and are similar in terms of system type and output. In the case of a non-residential building, this obligation does not apply if the building is equipped with a building automation and building control system. Here, too, it becomes clear how important building automation will be in the future, as it can be used to fulfill the operator obligations.

According to § 75 GEG (implementation and scope of the inspection), the inspection of an air conditioning system or a combined air conditioning and ventilation system includes measures to check the components that influence the efficiency of the system and the system dimensioning in relation to the cooling requirements of the building. § Section 76 GEG stipulates that the inspection should be carried out for the first time in the tenth year after commissioning. Thereafter, the system must be inspected every ten years at the latest. An inspection may only be carried out by a competent person.

Fundamental changes in the GEG are mainly found in the obligation to use building automation. Section 71a requires building automation to be state of the art for the first time. This has a particular impact on the design of the regulation of HVAC systems and the operator's inspection obligation under Section 74. Without building automation, operators are subject to strict obligations to inspect air conditioning and cooling systems every ten years. Due to this long period of time, there is also a risk for operators that systems will not have the expected energy efficiency over a long period of time. The malfunction of a system results in high costs, which are usually recognized too late. In this respect, operators are advised to implement building automation and monitoring at an early stage so that the systems are continuously monitored and malfunctions are detected in real time.

Author: *Prof. Christoph Kaup is Managing Partner of Howatherm Klimatechnik GmbH, Brücken, and Honorary Professor at the Environmental Campus Birkenfeld for Energy Efficiency and Heat Recovery (Trier University of Applied Sciences). He is also head of the technical centre for ventilation and air-conditioning technology, chairman of the board of the Fachverband Gebäude Klima (FGK), Ludwigsburg, a member of various standardization bodies and guideline committees and a member of the working group of lecturers for air-conditioning technology. (Image © Kaup)

The specific requirements resulting from the GEG for the individual trades were/will be shown with the support of various experts from the trades concerned from May to August 2024:

Part 1: General technical requirements (see cci273251)

Author: Christian Wild, Managing Director of Iconag Leittechnik GmbH, Idar-Oberstein

Part 3: Requirements for the heating and hot water supply trade

Author: Prof. Michael Krödel, Director of IGT - Institut für Gebäudetechnologie GmbH, Neubiberg

Part 4: Requirements for energy management and building automation management

Authors: Christian Wild (see below) and Christoph Zeis, Managing Director of Energiedienstleistungsgesellschaft Rheinhessen-Nahe GmbH, Nieder-Olm

Powered by ModuleStudio 1.3.2